- The Saturday Shareholder

- Posts

- 7 Ways To Use Benjamin Graham's Margin Of Safety Principle To Minimize Mistakes (And Losses)

7 Ways To Use Benjamin Graham's Margin Of Safety Principle To Minimize Mistakes (And Losses)

Read Time: 6-minutes

A big thank you to our sponsor for helping keep this newsletter free to the reader:

Money Wisdom focuses on the engine behind your investment portfolio: your income, spending, & savings habits. Money Wisdom shares top money strategies, principles, & frameworks to help you grow your investment portfolio and achieve financial freedom.

Today, we're going to look at 7 ways to use Benjamin Graham's Margin of Safety principle to minimize mistakes (and losses).

While the Margin of Safety principle holds immense value in the context of valuing investments…

“A margin of safety is necessary because valuation is an imprecise art, the future is unpredictable, and investors are human and do make mistakes.”

— Seth Klarman

— Investment Wisdom (@InvestingCanons)

12:19 AM • May 24, 2024

…Knowing additional investing contexts to apply it to makes our investing process that much more robust:

"The three most important words in investing: Margin of Safety."

And helps us to avoid common mistakes.

A double win.

So, let's get started.

1. Valuation:

In case you missed last week's edition, a Margin of Safety is a "cushion" in an investment's price that we require before purchase. It's best illustrated with an example:

Let's assume our estimate of a stock's price is $50. We will wait until the stock drops to $30—a 40% margin of safety ($50-30/$50)—before buying.

This minimizes the downside, maximizes the upside, and gives us some "breathing room" in case our estimate of the stock's value is wrong.

So, the essence of the Margin of Safety mental model is giving ourselves a cushion, a buffer, or a high hurdle—and this principle can be applied to other areas of investing.

In fact, this is what Benjamin Graham had to say in the last chapter of his book "The Intelligent Investor":

"[Margin of Safety] is the thread that runs through all the preceding discussion of investment policy—often explicitly, sometimes in a less direct fashion."

2. Shorting Investments:

If you're unfamiliar with the concept of shorting, here's a quick primer. Essentially, you borrow shares from another investor, sell those shares, and hope the stock price decreases so you can buy them lower.

It's still buy low, sell high, except you reverse the order.

A big issue with shorting is the risk-to-reward relationship, as described by Mohnish Pabrai:

"Warren Buffett does not short individual stocks. The Oracle of Omaha is on record saying that he and Charlie Munger have never been wrong about companies they thought were great short candidates, but they’ve almost always been wrong on the timing. Once you short a stock, there is no way to predict when the price will fall.

Why take a bet where the best return is 100% and the downside is unlimited?"

This risk-to-reward relationship seems antithetical to the Margin of Safety principle. So, most investors would probably be wise to avoid shorting.

Buffett reinforces this notion:

"[Shorting] is a tough way to make a living.

It’s very easy to spot phony stocks and promoted stocks, but it’s very hard to tell when that will turn around.

And somebody that’s promoted a stock to five times what it’s worth, may very well promote it to ten times what it’s worth, and if you’re short, that can get very painful.”

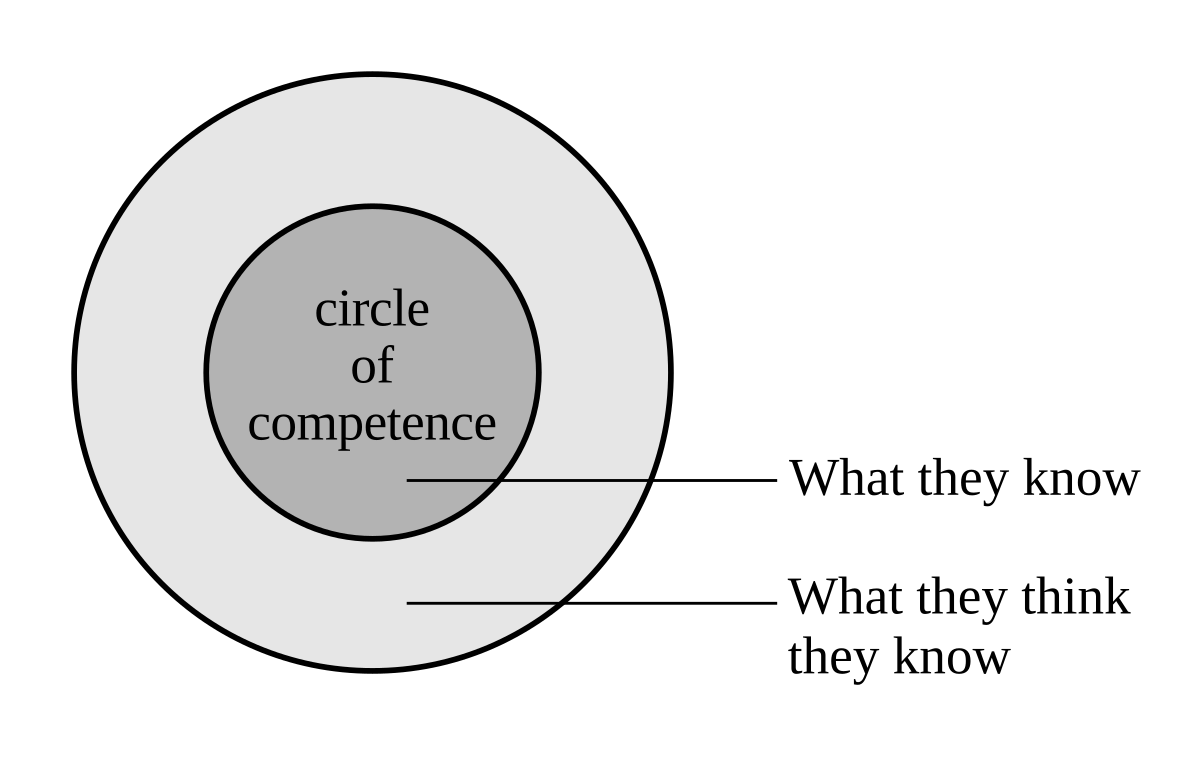

3. Circle of Competence:

“Knowing the edge of your own competency is very important. If you think you know a lot more than you do, well, you’re really asking for a lot of trouble.”

Knowing what you know—your circle of competence—and what you don't is critical. So much so that it's not that important to have a huge circle:

"The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.”

So, how do we apply the Margin of Safety here?

It's probably best to assume our circle of competence is a bit smaller than it actually is.

So that we have a buffer before we get into the "What they think they know" area here:

As Buffett put it:

“If we have a strength, it is in recognizing when we are operating well within our circle of competence and when we are approaching the perimeter.”

Better to be safe than sorry.

4. Our "Information Diet":

With the ubiquitous nature of social media and various other news sources today, it's more important than ever to guard our "Information Diet." Or the sources of which we consume investing-related information.

For one, destructive emotion can spread in an instant:

"Fear spreads like you will not believe."

And we want to take advantage of emotion, rather than be susceptible to it.

Plus, much of what grabs headlines today will be irrelevant tomorrow:

A good test when reading the news is to constantly ask, "Will I still care about this story in a year? Two years? Five years?"

So, we must set a high bar, a Margin of Safety, for who we follow and the news sources we consume.

Only curating information sources that communicate calmly, rationally, and bring quality insight.

Or as Munger put it:

“I try to get rid of people who always confidently answer questions about which they don’t have any real knowledge.”

— Charlie Munger

— Investment Wisdom (@InvestingCanons)

4:49 PM • Apr 9, 2024

5. The Investing Vs. Speculating Threshold:

Benjamin Graham made the important distinction between investing and speculating pretty simply:

He said investors evaluate "the market price by established standards of value," while speculators "base [their] standards of value upon the market price."

In other words, a speculator isn't making their own estimate of a stock's value, but simply gambling another person will pay more for it.

On the other hand, an investor believes the stock will go up because it's currently trading significantly below a conservative estimate of the stock's value—and, eventually, other investors will recognize this difference.

So, how do we apply a Margin of Safety within this context?

Graham gave us the key. We ask ourselves a single question:

"If there was no market for these shares, would I be willing to have an investment in this company on these terms?"

By imagining a world with no market quotations, it creates a high hurdle or Margin of Safety, by forcing us to come up with an estimate of the stock's value…

We have to have conviction in our estimate, because it may be a while before we can sell it to another investor.

We can't simply hope another investor will be around to buy our shares at a higher price next week.

6. Our Experience Requirement:

Let's do a thought experiment.

Let's imagine we have to choose one portfolio manager to manage all of our retirement money.

What are some of the criteria we would evaluate?

For one, we'd probably research how much experience they have.

Now, let's ask ourselves: how much experience do we have?

The answer may be uncomfortable to some of us…

And that's the point.

If we want to be safe, if we want to apply a Margin of Safety here, we probably would be wise to require ourselves to have a significant chunk of experience before turning too much of our portfolio over to ourselves.

///

You’ve made it quite a ways, so you’re probably finding this valuable. Join others who get The Saturday Shareholder automatically sent to their email every Saturday. Join free here.

///

7. Our “Do-It-Ourselves” Portfolio Allocation:

How much we allocate to our "Do-It-Ourselves" investing bucket is a major decision, of course, as well.

Too much, too soon, and we could end up with unacceptable losses.

Benjamin Graham touched on this topic, proposing paper trading (simulating investing without real money) for a year. Then:

"If you enjoyed the experiment and earned sufficiently good returns, gradually assemble a basket of stocks—but limit it to a maximum of 10% of your overall portfolio (keep the rest in an index fund). And remember, you can always stop if it no longer interests you or your returns turn bad."

Limiting our allocation to 5 to 10% builds in a Margin of Safety…

One of the most important mental models in all of investing.

Conclusion:

Those are the 7 ways to use Benjamin Graham's Margin of Safety principle to minimize mistakes (and losses). Let's recap:

Valuation: Require a Margin of Safety between our estimate of an investment’s value & the market price.

Shorting Investments: Probably wise to avoid.

Circle of Competence: Assume it's smaller than actuality.

Our “Information Diet”: Only follow the best accounts & news resources.

The Investing vs. Speculating Threshold: Are we willing to invest without a market full of price quotes?

Our Investing Experience Requirement: More is better.

Our “Do-It-Ourselves” Portfolio Allocation: Less is more.

Well, that's all for this week.

I hope you found it helpful.

See you next Saturday.

Two resources I think you might like:

Book Summaries: One of the most important lessons from Charlie Munger is to strive to become a little bit wiser each day. To accelerate my learning on everything from investing & decision-making to negotiating & habit-building, I use Blinkist (I’m excited to share I recently partnered with Blinkist. Thank you to the Blinkist team as their affiliate program helps keep this newsletter free to the reader). Blinkist offers easily readable book summaries to help you get the most valuable ideas from the most popular books. You can check out Blinkist here.

Mental Exercises: To paraphrase Morgan Housel, the common factor among elite investors is they have complete control over the space in between their ears. Financial news networks and social media can create a lot of "noise" for investors. To stay focused and calm, I like to use Headspace (I don't receive any compensation from Headspace currently). Headspace offers mindset and breathing exercises to help you keep control over the space between your ears. You can check out Headspace here.

Disclaimers

This material is not investment advice. No responsibility for loss occasioned to any person or corporate body acting or refraining to act as a result of reading this material can be accepted by the publisher. Additional disclaimers here.